|

|

In the British Caribbean, many freed slaves had little choice

but to continue to work for their old masters. Production was still

mainly aimed at supplying the external British market and it was

a white British elite who remained in overall control of economic

activity.

The British Caribbean islands differed from other British colonies

in that the original inhabitants had long since died out and most

of the people were living there as a result of some form of slavery.

From 1845 onwards, plantation owners could draw upon so-called ‘coolie-labour’,

in addition to the ex-slave population. ‘Coolies’ referred

to thousands of indentured Indian labourers who were brought to

the colonies. The labourers worked in slavery-like conditions,

contractually bound to their employers for fixed periods. Prior

to the development of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, white British

indentured labourers had worked on the plantations, along with

thousands of Irish Catholics who were shipped out following Cromwell’s

brutal campaigns in Ireland in the mid-seventeenth century. These

people, who struggled to adjust to the difficult climate, were

too few in number to sustain production so slaves had been transported

from Africa to work beside them. In the mid-nineteenth century

the British government introduced Chinese labourers to the colonies,

adding to the cultural melting pot and the multiple ethnic reference

points that form Caribbean identity. Around 40,000 African indentured

labourers were also brought in at this time.

Novelist and cultural critic Mike Phillips writes:

In the Caribbean, the African descended majority had no pre-existing

claims on the land, no widely accepted institutions which predated

slavery and no historical continuity before their arrival in the

region. Therefore national identity had to be created from scratch,

and using only what was available. Given the polyglot nature of

the community and their total isolation from previous custom and

practice, the Black majority in the Caribbean territories ruled

by Britain had no alternative but to echo and mirror the life of

the British.

The injustices of the old trade lived on after abolition in discrimination

based upon skin colour. In Bermuda, for example, a system of racial

segregation similar to that of the southern states of the USA existed

until 1959, restricting the public places where black people could

go. More subtle forms of discrimination also existed. When purchasing

slaves or hiring employees, plantation owners tended to favour

the lighter-skinned for house work, the darker ones for field work,

thereby instilling a class distinction based on degrees of blackness.

In Small Island, when Celia Langley says Jamaicans must help with

the war effort as the Nazis would bring back slavery, her friend

Hortense reflects:

I could understand why it was of the greatest importance to her

that slavery should not return. Her skin was so dark. But mine

was not of that hue – it was the colour of warm honey. No

one would think to enchain someone such as I. All the world knows

what the rousing anthem declares: ‘Britons never, never,

never shall be slaves’.

This ‘grading’ of skin, informed by Western rather

than African aesthetics, became an accepted practice among both

black and white. A light-brown skin was perceived for many years

as being more attractive and more civilised than a dark one.

In an interview with the Guardian in 2004, Andrea Levy said:

My parents came from a class in Jamaica called ‘the coloured

class’. There are white Jamaicans, black Jamaicans and coloured

Jamaicans. My parents’ skin was light. They were mixed race,

effectively. They came to Britain with a kind of notion that pigmentation

represented class. They didn't necessarily have more money or education,

but because they were somehow closer to being white, this was seen

as a badge of pride.

In Small Island the character Hortense is astounded on her first

full-day in Britain that Queenie should try to reassure her by

saying, ‘I’m not worried about what busybodies say.

I don’t mind being seen in the street with you’. The

well-spoken, honey-coloured, white-gloved Hortense thinks if anyone

is to be ashamed it is her for being seen with a woman ‘dressed

in a scruffy housecoat with no brooch or jewel, no glove or even

a pleasant hat to life the look of her’. She has yet to realise

that to the British she is black and therefore an object of curiosity,

contempt and even hostility.

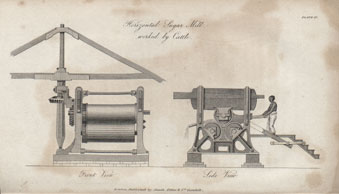

Sugar mill worked by cattle from The Nature and Properties of the

Sugar Cane by George Richardson Porter, 1830 (Bristol Library Service).

After abolition, the slave trade continued to shape the colonisation

of Africa. The failure of some African states to find alternative

sources of income to that of slave trading encouraged Britain to

interfere with African affairs. Previously, Europeans had not ventured

far into Africa and had had to obtain permission from local kings

and chiefs before engaging in trade for slaves in the designated

trading areas. Now that slavery was deemed immoral, British colonisation

was ‘offered’ as a means of developing more respectable

forms of trade. As the other colonial powers gradually abandoned

the slave trade too, a similar justification was used by them to

start exploiting Africa for their own ends. At first, European

trading activity remained largely confined to the Western coast

and the Cape, but intense rivalry between the colonial powers by

the late-nineteenth century led to the ‘Scramble for Africa’ in

which areas of the interior that previously were only informally

influenced by the Europeans came directly under their control.

Describing the jostling for position, a British politician wrote

in 1892:

We are to effect the reconquest of Equatoria and occupy the Albert

Lakes and the whole of the basin of the Upper Nile, Why? For fear

of the French, the Germans, the Belgians etc etc.

Africa was a source of gold, rubber, cocoa, diamonds, palm oil,

ivory, pepper and other valuable trading goods. The colonisation

of Africa by the European powers contributed to the inequalities

that exist today between the prosperous West and the impoverished,

debt-ridden African countries. In addition, because the Europeans

ignored centuries of tribal and cultural differences when carving

up the continent, with the coming of independence has also come

the outbreak of long-simmering civil wars.

The Indo-Caribbean community. Read

more...

African missionaries. Read

more...

|

|

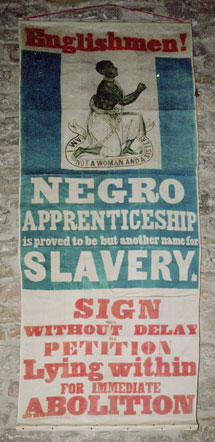

Anti-apprenticeship banner.

Read

more...

Jamaican sugar plantations. Read more...

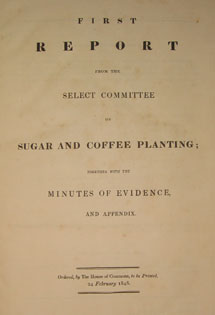

The 1848 Select Committee.

Read

more...

The Morant Bay Rebellion.

Read

more...

Sugar cane harvest near Georgetown, Guyana, 1958 (Science and

Society/NMPFT - Walter Nurnberg).

|

|