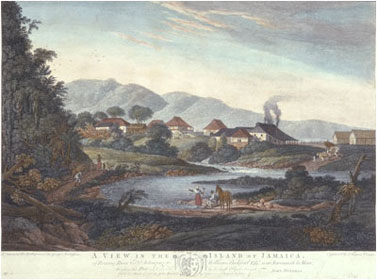

William Beckford's Roaring River Estate, Jamaica. This coloured engraving by Thomas Vivares from a painting by George Robertson was published in 1778.

There was such a demand for sugar in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that much of the natural vegetation of the Caribbean islands was cleared to create the large plantations needed for its growth. Many of the small farms established by early settlers for the growing of tobacco and cotton were bought up and incorporated into the plantations.

William Beckford of Somerley inherited four sugar plantations in Jamaica, which he personally supervised. In 1790 he published a two-volume work called A Descriptive Account of the Island of Jamaica which includes his observations upon the organisation of the island's sugar trade. In the opening pages he gives the following table showing the number of estates, settlements, slaves, cattle and sugar production for each of Jamaica's three counties.

| Counties |

Sugar Estates |

Other Settlements |

Slaves |

Produce. Hogsheads of Sugar |

Cattle |

| Middlesex |

323 |

917 |

87,100 |

31,500 |

75,000 |

| Surry |

350 |

540 |

75,600 |

34,900 |

80,000 |

| Cornwall |

388 |

561 |

90,000 |

39,000 |

69,500 |

| Total |

1,061 |

2,018 |

255,700 |

105,400 |

224,500 |

1 hogshead = approx 16cwt = approx 812 kg

At the time Jamaica had a white population of around 23,000 people.

In the following extract from the work's first volume Beckford describes the beauty of the island.

The first appearance of Jamaica presents one of the most grand and lively scenes that the creating hand of Nature can possibly exhibit: mountains of an immense height seem to crush those that are below them; and these are adorned with a foliage as thick as vivid, and no less vivid than continual. The hills, from their summits to the very borders of the sea, are fringed with trees and shrubs of a beautiful shape, and undecaying verdure; and you perceive mills, works, and houses, peeping among their branches, or buried amidst their shades.

He describes a sugar plantation as being 'like a little town':

it requires the produce, as well as the industry of every climate; and I have often been surprised, in revolving in my mind the necessary articles that the cane requires and consumes, how intimately connected is every thing that grows, and every thing that labours, with this very singular, and at one time luxurious, but now very necessary, as it is deemed to be a highly useful and wholesome, plant.

|

|

These extracts were copied from Bath Central Library's edition of the book. Transcribed excerpts can also be read on a genealogical website created and maintained by David Bromfield.

William Beckford of Somerley was the cousin of the more famous William Beckford of Fonthill who never set foot in Jamaica, but who inherited the bulk of the Beckford sugar fortune that was based on over 20 Jamaican plantations on which worked thousands of slaves. William of Fonthill used his inheritance to live a riotous life of excess and scandal. He was a designer, author, architect and gardener, and he built Beckford Tower at Bath. The Open University produced a programme on the contrasting life of the two Williams called Sugar Dynasty

Thomas Kerr was a sugar planter in Antigua. His book A Practical Treatise on the Cultivation of Sugar Cane, and the Manufacture of Sugar was published in 1851. Kerr aimed to improve techniques in all stages of sugar production in the West Indies as a way of offsetting the changes in labour brought about by the emancipation of the slaves. This extract summarises the problems then faced by planters.

The earlier the operation of digging the cane-holes could be performed, the more creditable to the judgment and exertion of the Planter, although this depended, in some degree, on the period of the crop being finished, on the time occupied in preparing the land for planting provisions for the support of the slaves, or for sale, and, since the abolition of slavery, in a very great measure on the number of labourers who could be procured.

From the completion of the operation of "holing", till the canes completely covered the surface, constant weeding was required, and large gangs were continually employed. No other method of weeding than hand-hoeing was possible, from the peculiar formation of the angular holes and banks. In fact, the whole system, from the breaking up of the first clod of earth, to the rolling of the hogshead of sugar into the waggon, appeared to have been expressly contrived for employing the greatest possible amount of human labour. The large amount of capital, therefore, required for the labourers, rendered sugar planting, except under peculiarly favourable circumstances, very far from being so remunerative as is generally supposed.

A longer extract can be read on the website of the University of Western Ontario |