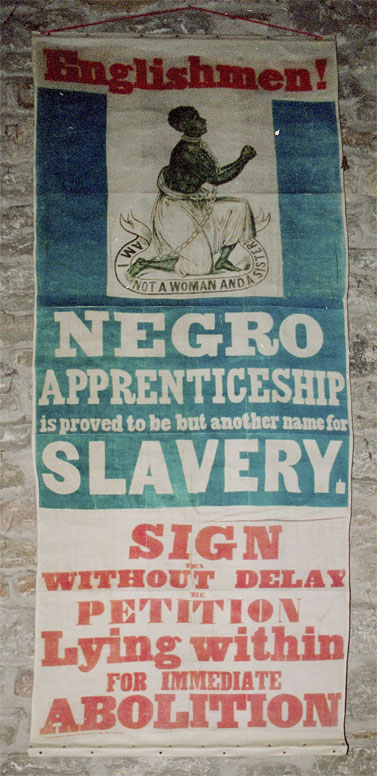

Banner promoting the campaign to end apprenticeships. Image courtesy of British Empire and Commonwealth Museum.

The Emancipation Act of 1833 came into effect on 1 August 1834. All British-owned slaves under the age of six years were immediately freed, but older slaves were to be apprenticed for a fixed period of up to eight years, leaving them little better off than they had been under slavery. The ex-slaves continued to work for their former owners for 45 hours a week, receiving food, clothing, housing and medical treatment, but no money. For the rest of their time they were allowed to work for pay either on their home plantation or elsewhere.

Some owners ignored the apprenticeship scheme and freed their slaves immediately as they calculated that it was cheaper to hire workers for a daily wage when needed than to feed and house unpaid apprentices. Compulsory apprenticeships were enforced in Guyana, but, anticipating a labour shortage, plantation owners there also recruited over 5,000 full-time freed workers from the islands of Barbados, St Kitts, Antigua, Montserrat and Nevis.

Under pressure from abolitionists, the British Parliament eventually voted in favour of complete emancipation of the former slaves. This came into effect on 1 August 1838.

The following extract is from a poem written by the Cornish poet John Harris to celebrate the end of slavery.

'The Fall of Slavery' (1838)

Prayer is heard, the chain is riven,

Shout it over land and sea;

Slavery from earth is driven,

And the manacled are free;

Brotherhood in all the nations;

What a glorious Jubilee!

God has answered, fall before Him,

Laud His majesty and might;

On thy knees, O earth, adore Him:

Now the black is as the white;

Hallelujah! hallelujah!

Every bondsman free as light.

Whip and scourge, and fetter broken,

Far away in darkness hurled;

This a grand and glorious token,

When millennium fills the world.

Hallelujah! O'er the nations

Freedom's snowy flag unfurled. |

|

In Jamaica many ex-slaves abandoned the plantations, taking over wasteland to cultivate as their own. By 1860 it is estimated that 40 per cent of the island was owned by black people. Elsewhere in the Caribbean, however, where there was no spare land available, ex-slaves had no option but to continue working on the old plantations.

The following is an extract from an address by Ralph Waldon Emerson delivered in Concord, Massachusetts to the Ladies' Antislavery Society on 1 August 1844, marking the tenth anniversary of the enforcement of the Emancipation Act. North American slaves had yet to be freed and none of the churches in Concord would let the society hold its convention on their premises from fear of the controversy it would stir up.

The First of August, 1838, was observed in Jamaica as a day of thanksgiving and prayer. Sir Lionel Smith, the governor, writes to the British Ministry, "It is impossible for me to do justice to the good order, decorum, and gratitude, which the whole laboring population manifested on that happy occasion. Though joy beamed on every countenance, it was throughout tempered with solemn thankfulness to God, and the churches and chapels were everywhere filled with these happy people in humble offering of praise."

The Queen, in her speech to the Lords and Commons, praised the conduct of the emancipated population: and, in 1840, Sir Charles Metcalfe, the new governor of Jamaica, in his address to the Assembly, expressed himself to that late exasperated body in these terms. "All those who are acquainted with the state of the island, know that our emancipated population are as free, as independent in their conduct, as well-conditioned, as much in the enjoyment of abundance, and as strongly sensible of the blessings of liberty, as any that we know of in any country. All disqualifications and distinctions of color have ceased; men of all colors have equal rights in law, and an equal footing in society, and every man's position is settled by the same circumstances which regulate that point in other free countries, where no difference of color exists. It may be asserted, without fear of denial, that the former slaves of Jamaica are now as secure in all social rights, as freeborn Britons." He further describes the erection of numerous churches, chapels, and schools, which the new population required, and adds that more are still demanded. The legislature, in their reply, echo the governor's statement, and say, "The peaceful demeanor of the emancipated population redounds to their own credit, and affords a proof of their continued comfort and prosperity."...

It was shown to the planters that they, as well as the negroes, were slaves; that though they paid no wages, they got very poor work; that their estates were ruining them, under the finest climate; and that they needed the severest monopoly laws at home to keep them from bankruptcy. The oppression of the slave recoiled on them. They were full of vices; their children were lumps of pride, sloth, sensuality and rottenness. The position of woman was nearly as bad as it could be, and, like other robbers, they could not sleep in security. Many planters have said, since the emancipation, that, before that day, they were the greatest slaves on the estates. Slavery is no scholar, no improver; it does not love the whistle of the railroad; it does not love the newspaper, the mailbag, a college, a book, or a preacher who has the absurd whim of saying what he thinks; it does not increase the white population; it does not improve the soil; everything goes to decay.

The full address can be read on the website of

the Walden

Woods Project. |