|

|

Despite its urban sprawl, Bristol can still be seen as a

collection of distinctive geographic areas, each with its own

history, which together give the city its identity. Here is information

on just a few of them.

The Centre

Bristol's centre was originally near Bristol Bridge, at the crossroads

formed by the High Street, Wine Street, Corn Street and Broad

Street. When people refer to The Centre today they usually

mean the area that was once the site of the Tramways Centre

(the hub for the city's tram routes) between Broad Quay and

St Augustine's Parade. This area was redeveloped in the 1990s

in an effort to overcome congestion problems and to provide

a more clearly defined and exciting public space. Critical

reaction to the scheme has been less than enthusiastic, but

there was little affection for how it looked before either.

The

Centre, c 2005.

Many years ago, the place where

the fountains now play used to be a busy dockside. The waters

of the northern section of St Augustine's Reach – a man-made

channel dug in the thirteenth century during the diversion of

the River Frome – were covered over in the 1890s because of increased

demands from road traffic. Its water still flows under the tarmac

and paving stones. This is what the area looked like in the late

eighteenth century when Bristol was at its height as a trading

port.

Broad Quay, Bristol, attributed to Philip

Van Dyke, c 1760 (Bristol's Musems, Galleries and Archives).

The Centre is the site of the Bristol Hippodrome, pictured below,

which was built in 1912. West End shows that have been premiered

here include Guys and Dolls (1953) with Sam Levene and Stubby

Kaye, The Music Man (1961) with Van Johnson, and the Disney-Sam

Mackintosh production of Mary Poppins (2004).

In the Gallery by

Alexander J Heaney, c 1928 (Bristol's Museums, Galleries and

Archives).

Temple

The lead statue of King Neptune in The Centre's pedestrianised

area has been moved several times since it was cast in 1722.

Here it is seen in its first home near Temple Church when it

was still painted in colour rather than its current grey.

The

Neptune, Church Lane, near Temple Church by George W Delamotte,

1825 (Bristol's Museums, Galleries and Archives).

The

area of Temple, south of the Bristol Bridge, was given to the

Knights Templar in 1145 by Robert, Earl of Gloucester and it

is often referred to as the city's first suburb. The knights

were soldier-monks who guarded pilgrims travelling to the Holy

Land. Bristol gained control of Temple following the Reformation

when the monasteries were abolished. It was once the centre of

Bristol's weaving trade and the guild had its chapel in Temple

Church. This area was among those targeted by German bombers

in the Second World War and the church was severely damaged during

the Blitz. (Read about the Blitz in the Bristol at War story

on The

Siege website.) The bombed-out shell is now a listed monument, owned

by English Heritage. The tower is not leaning because of the

bombing: it had already started to tilt when it was being built

in the fourteenth century, but has managed to survive.

Temple

Church pictured on the Church

Crawler website.

Queen Square

Elegant Queen Square, one of the largest residential squares

in Europe, was named in honour of Queen Anne when she visited

the city in 1702. It was built on The Marsh, which had previously

been used as an archery training ground, bowling green, boat

yard and for general recreation. The square was once home to

some of Bristol's wealthiest merchants as well as being the

site of the first American Consulate in Britain, established

in September 1792.

Queen Square Bristol from the North West

Corner by Thomas L Rowbotham, 1827 (Bristol's Museums, Galleries

and Archives).

The square was also the focus

of the Bristol Riots of 1831, which stemmed from discontent at

the corruption of city officials and the defeat of the Reform

Bill. Many buildings were burnt to the ground during the rioting

and several people were killed. Of those arrested by the authorities,

four were hanged and nearly 100 transported to the colonies.

Bristol

Riot, 1831 (Bristol's Museums, Galleries and Archive).

Although the destroyed buildings were gradually replaced, the

square failed to recover its former prestige, most of the private

homes becoming increasingly downmarket lodging houses, and during

the late 1930s it suffered the indignity of having a dual carriageway

built across it. In the 1990s, Bristol City Council initiated

plans to renovate the square, removing the dual carriageway,

restoring gravel paths, digging up tarmac to reveal the original

setts (cobbles) beneath and planting mature saplings to fill

gaps between the trees. The official re-opening of the square

took place in September 2000 and it is once again one of the

most attractive public spaces in the city. The surrounding buildings

are now nearly all used as office space.

Queen Square, c 2005

(Destination Bristol).

Clifton

Many of the merchants who first lived in Queen Square had already

started to move out to the new terraces of Clifton before the

Riots took place. The manor of Clifton – then known as Clistone

– is mentioned in the Domesday book (1085). It remained a small

hamlet of scattered farms and houses until the 1700s when it

experienced a building boom, having been purchased by the Society

of Merchant Venturers in 1676. Wealthy city-dwellers were attracted

by its clean air and the views across the downs and gorge,

and the population rose from around 450 in the early eighteenth

century to nearly 4,500 in the 1801 census. Clifton was incorporated

into the city in 1835.

An early nineteenth-century watercolour

of Clifton Gorge by Marianne Smith (private collection). This

predates the building of Brunel's Suspension Bridge but the Clifton

Observatory can be seen in the distance.

Visitors

were also attracted to the hot springs here in Clifton and at

nearby Hotwells, coming in the summer season before moving on

to the even more fashionable Bath spas in the winter. The French

Wars of the 1790s brought bankruptcy to many of the merchants

and property speculators who had invested in the development

of Clifton, bringing several of the building projects to a halt.

Despite this set back, significant terraces and, later, villas

continued to be constructed into the mid-nineteenth century and,

architecturally, Clifton remains one of the most impressive areas

of the city.

Royal York Crescent, built c 1791-1820,

photographed c 2005 (Destination Bristol).

St Paul's

St Paul's was developed as a city suburb on Bristol's eastern

fringe in the late eighteenth century to accommodate the rapid

growth of the local population. It was originally home to the

merchant class and Portland Square, now mainly used for offices,

was once one of the city's most desirable addresses. St Paul's

Church, which is to the east of the square, was known as the

Wedding Cake Church because of its unusual tiered tower. It

was completed in 1794, but was forced to close in 1988 because

of its dwindling congregation. It is now home to Circomedia,

the circus skills groups, and won the top accolade for 'Community

Benefit' in the 2007 Royal Institute for Chartered Surveyors

Awards in the South West.

St Paul's Church pictured on the About

Bristol website.

In the nineteenth century, St Paul's was an industrialised

area, having a particular speciality in boot- and furniture-making

businesses. By the Second World War it had become severely neglected

and run-down, with only those too poor to move away to the safety

and comfort of the suburbs remaining in residence there. Some

of the more decrepit terraces were replaced by new low-rise flats

in the postwar period but this did little to stop the continuing

blight. When migrants from the Caribbean began arriving in Bristol

in the 1950s, it was one of the few areas in the city they could

afford to live. Landlords let the buildings decay further, having

no incentive to improve them as they knew their tenants were unlikely

to find any alternative accommodation in the city. Despite the

poverty and social inequality, with its associated problems of

drugs and crime, there is a positive community spirit in St Paul's,

marked by initiatives such as the Afrikan-Caribbean Carnival, which

was founded in 1967, and by the St Paul's Unlimited scheme, which

aims to make constructive changes to the environment and lives

of the residents.

Image of the carnival pictured

on the St

Paul's Carnival website.

Bedminster

Bedminster, a royal manor listed in the Domesday Book and with

Roman origins, did not officially become part of Bristol until

the boundary changes of the 1890s, though it had long been

considered as a city suburb. It lies south of the New Cut,

a bypass to the river Avon running from Temple Meads to Hotwells,

which was created in the early nineteenth century during construction

of the non-tidal Floating Harbour.

Aerial view of the Avon and

the New Cut in the 1930s, with Bedminster to the right of the

picture.

The area prospered during the Industrial Revolution

when it was home to collieries, brickyards, iron founderies,

tanneries, glassworks, potteries, breweries, and glue-, paint-

and paper-making factories. Between 1801 and 1851, the population

rose from just over 3,000 to nearly 19,500 as people were attracted

by the employment opportunities, and new or extended housing developments overflowed

into Windmill Hill, Totterdown, Southville and Bedminster Down.

By the end 1880s, when the Wills tobacco factory moved to here

from Redcliffe, the population was nearly 80,000.

Headquarters

of W D and H O wills in East Street, Bedminter c 1900.

Bedminster suffered badly during the bombing of

the Second World War and also in the postwar redevelopment of

the city, but has undergone a renaissance in recent years, in

part thanks to the presence of the Tobacco Factory theatre and

bar, and to a range of independent shops and businesses along

North Street.

Sea Mills

During the slum clearances in the centre of Bristol after the

First World War, people were encouraged to move from the city

centre to new housing on the suburban fringes such as the Seas

Mills Municipal Estate. Houses on the estate had their own

gardens, indoor sanitation, hot water and lighter, better equipped

kitchens. Fields and parks nearby provided play areas for children

away from the streets, and new schools were also built. The

disadvantage of these new estates was that they had few shops

and were a long distance from work for those still employed

in the city centre.

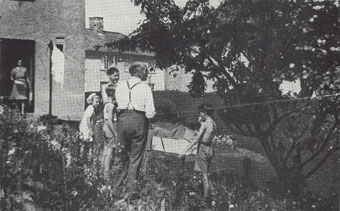

A family enjoying their new Sea Mills'

garden in the 1930s.

In the housing shortage that followed

the Second World War, temporary pre-fabricated houses were erected

at Sea Mills, some of which are still occupied.

Pre-fabs in Sea

Mills, pictured on the About

Bristol website.

There had been a settlement at Sea Mills

in Roman times and an attempt to build a dock here in the eighteenth

century, but it was these postwar developments that made the

area what it is today. Other areas that were originally established

as garden-suburbs for the city included Knowle West and Fishponds.

|

|

Tell us about the area of

Bristol in which you live, study or work. Submit your

contribution via the My

Bristol page. |

| |