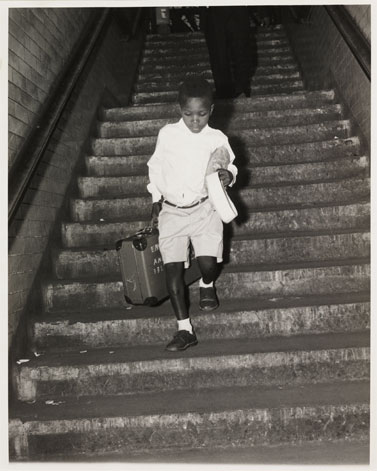

Young boy at Victoria Station, London, 24 June 1962. The original caption for this photo read 'Luggage collected, this young fellow is ready to start a new life in Britain'. Image courtesy of Science and Society Picture Library/ NMPFT Daily Herald

It was usual in the first decade or so of Caribbean immigration for men to come on their own to find a job and somewhere to live before sending for their wives and families. Sometimes children would be left behind with grandparents or other relatives for one or two years until their parents had established themselves in their new homes. On arrival in Britain the children would be faced with re-establishing a relationship with their families in a bewildering and sometimes intimidating environment. It could be both traumatic and exciting.

Author and entertainer Floella Benjamin came to Britain from Trinidad with her sister and brothers in 1960. She had not seen her father for nearly two and a half years and her mother and youngest brother and sister for 15 months. This extract is from her autobiography Coming to England and describes her arrival in London.

I soon began to notice people staring at us. I thought it was because we were wearing brightly coloured clothes, our very best clothes. They all had on such dull, drab colours: black, navy and grey, as if they were going to a funeral. What I didn't realize was that staring was something I was going to have to get used to.

At last we turned into the road which was to be our home for the next month: 1 Mayfield Avenue, a two-storey semi-detached red brick house with a brown door. I felt nervous and anxious as Marmie opened the door with her key. She led us up the narrow staircase and along a landing. Then she unlocked another door. As she opened it she said, 'Welcome to your new home.' I slowly crept into the dark, dingy room and looked around. I took in the contents of the room: a double bed, table, couch, some chairs, cupboards and a wardrobe. Was this it? Surely this couldn't be what we had travelled thousands of miles for. Was I to start my new life in this cluttered room? I felt a swell of disappointment rising inside. The whole day had left me emotionally drained and to crown it all I had ended up in one room which all of us would have to share. I hadn't considered that fact that it was all my parents could afford, that they had saved every penny to send for us to be together. All I knew was this was not what I wanted my new home to be. My dreams were shattered and scattered. I suddenly burst into hysterical tears. Sandra started to cry too, then the boys joined in. Nothing Marmie said could comfort us. She started to cry as well and began to prepare a meal. At least that was the one thing that hadn't changed - Marmie and her cooking.

Sir Herman Ouseley joined his family from Guyana in 1957 and went to school in South London. This interview extract in which he considers the conflicting pressures on young black people at that time is taken from the book Windrush: the irresistible rise of multi-racial Britain by Mike Phillips and Trevor Phillips. |

|

I think the conflicts that I saw in my own life in the late fifties were conflicts that I think that many other young black people were not prepared to take on - a different regime at home, in the school, on the streets, in the playground - and those were enormous conflicts to deal with because you're getting one pressure in the home, another one on the streets, seeing things happening around you, another pressure in the school and the playground. I think you started to see the emergence of a bit of rebelliousness. And then you had bodies like the police, you had social work interventionists, you had some parents who were finding it difficult to cope. And very often the threat, the very common threat to a lot of black kids was, you know, If you don't behave yourself I'll put you in a home. And a lot of black kids did end up voluntarily being placed in local authority care - in institutionalised care. So there was a pattern emerging in which there was rejection of jobs that might be available that black young people didn't feel they were going to take. And that was, I think, the start of the difficulties for some young black people coming of out school.

These extracts, also from Windrush: the irresistible rise of multi-racial Britain, illustrate the difficulties some children faced in their classroom where teachers had low expectations of black pupils, based in part on the unfamiliarity of the Caribbean accents.

I was the only black child in the school. And, funnily enough, one of the other things about that was they didn't even give me a test to see - it was a secondary modern school - they didn't even give me a test to see which grade I should be put in, you know, they just put me in the lowest grade. Then they had a sort of end of year examination and I moved up into the top class. But I remember a teacher, teaching Shakespeare and the soliloquy from Julius Caesar. And this teacher said, "Who can explain what this soliloquy means?" So I put my hand up, you know. And, of course the way I spoke then is not like I speak now, I had this funny Jamaican accent. And this teacher just rolled around. I felt so ashamed, that he was basically mocking me, you know, and I felt so ashamed. And I stopped, I really basically stopped going to school, because I felt so angry and ashamed. It still hurts to this day, you know, because it was bloody upsetting. And that was what it was like. You weren't expected to know anything and they just took the mickey. And that was then, 1949, '49, and it still hurts. Vince Reid who arrived in Britain on the Windrush at the age of 13

... I'd experienced primary school education in the Caribbean, and was brought specifically to Britain "to be educated", as it was put by my family. So I anticipated being able to attend secondary school and spend a lot of time being able to learn and develop skills that would enable me to make a way of life. I was also interested in thinking of long term careers, because this is always your goal as you grow up in the Caribbean, you either go into religion and the ministry, or you would become a lawyer, or a doctor, or something of that sort. And so I was very focused on the idea of making a career for myself when I arrived.

The school experience was confusing, because on the one level, most people in senior positions wanted to be helpful, but I don't think they really understood the emotions I was experiencing, having to come to terms with the racial issue, having to come to terms with an education system that was quite different from the one I'd experienced in the Caribbean, where we were a lot more formal and a lot more structured and set in relation to work that we had to do by certain times. A number of black kids got lost in the system 'cos they couldn't see ways into it. I was lucky, I had one or two school masters who I was able to relate to and find things that I could actually get my head stuck into. And also I had a lot of family support to enable me to really dedicate a lot of time to working and making something of my life. Russell Profitt who joined his family in the early 1960s at the age of around 12

I think what happened was that we come from the West Indies, where working-class people had middle-class ambitions. The whole society's motivated. Exam results are carried in the newspapers, as Oxford and Cambridge are carried in The Times here. You work your nails and your knuckles off to send your children to school and that was the only way that you can move up socially and economically. So when we came here, the white working class, on the other hand, have accepted, more or less, their role in society. We came with ambitions and that was the main conflict with the education department. So we would go to school - it still happens now - we would go to the schools and our children will tell the careers officer, "I want to be a doctor", "I want to be a lawyer", "I want to be an architect." And they look at you in amazement, because when they look at your family background - your father's a bus driver or a carpenter or whatever - and, as far as you're concerned, no way. So that was one of the main clashes. Eric Huntley who came to Britain from Guyana in 1957.

|